Thursday, September 28, 2006

The Great Transformation of Corporate Finance and its Impact on the Economy

So, how does the increasing resourcefulness of financial institutions affect the functioning of corporate governance? Well, in many ways as I will show. But let’s start with the cause of this evolution: the increasing variety of financial instruments, that is.

People that are familiar with the Swiss economy might remember the uproar that was created by Martin Ebner, when he first introduced a new equity instrument in

What is important for the question of corporate governance, is the fact that the introduction of this instrument had an important impact on the evolution of the financial markets in

A multiplicity of very complex instruments and ways of financing debt has been created recently. What is important for my purpose is that the issuing of this kind of debt instruments is less and less the exclusive hunting ground of commercial (or universal) banks. In fact hedge funds, who are often ready to take considerable risks, have become important actors on this market.

This evolution has, according to Gillian Tett, lead to an increased accessibility of finance notably for companies that are in financial trouble. One remembers the negotiations between ‘financially challenged’ companies and banks for new loans (e.g. Swissair). This situation has, according to Tett, considerably changed in recent years: “[W]hereas these companies would have once been forced to turn to commercial banks [in order to obtain new loans], there is now a growing tendency for troubled companies to use hedge funds or other sources of capital […] (FT

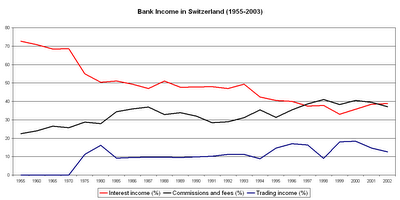

Now, what does this mean for the functioning of corporate governance? One important consequence is of course that the role of banks changes in important ways. Banks used to play a central role in the functioning of the economy especially in countries with strong universal banks – i.e. banks that are active both as commercial banks (loans) and investment banks (equity issuing etc.) - such as Switzerland and Germany. Universal banks grant loans to corporations, they issue equity for corporations, advise them in merger and acquisition activities and controlled, moreover, important portions of voting rights during the Annual General Meeting of these companies through a proxy voting system that allows them to vote for bank clients that did not wish to attend the AGM. This is why Continental European Corporate Governance Systems are usually called ‘bank-centred’ systems.

The central role of banks and their multiple channels of influence on industrial companies gave periodically rise to criticism of the power of banks and their damaging influence on industrial development. The most extreme theories postulated that banks consciously accepted the bankruptcy of a company that was under their controlled in order to get the maximum out of the company’s assets.

In

Be that as it may, the recent evolution of corporate finance led to a situation where industrial companies do not seem to rely so much on banks anymore, but they take out loans from other financial institutions or rise capital directly on equity markets (in the latter case, one speaks of disintermediarisation). Consequently, industrial companies are more and more independent from banks.

One important consequence of the disintermediarisation and the strategic reorientation of banks away from the loan business, which goes together with the increasing independence of industrial companies, is the anonymisation of relations between banks and industrial companies. In fact, credit activities are usually considered to be relationship-based activities, implying close personal ties between borrower and lender and an active monitoring by lenders of their loans. This was a central feature of Continental European corporate governance systems and limited the strength of market forces. Corporate finance through investment in equity, on the other hand, is market-based and does not necessitate any particularly close relationship between investor and issuer. This brings us to the downside of the increased independence of industrial companies from banks. By using more and more securitised finance instruments – as well for debt as for equity – companies become more dependent on financial markets. And this is precisely why we find so much change in corporate strategies in countries like