Thursday, September 28, 2006

The Great Transformation of Corporate Finance and its Impact on the Economy

So, how does the increasing resourcefulness of financial institutions affect the functioning of corporate governance? Well, in many ways as I will show. But let’s start with the cause of this evolution: the increasing variety of financial instruments, that is.

People that are familiar with the Swiss economy might remember the uproar that was created by Martin Ebner, when he first introduced a new equity instrument in

What is important for the question of corporate governance, is the fact that the introduction of this instrument had an important impact on the evolution of the financial markets in

A multiplicity of very complex instruments and ways of financing debt has been created recently. What is important for my purpose is that the issuing of this kind of debt instruments is less and less the exclusive hunting ground of commercial (or universal) banks. In fact hedge funds, who are often ready to take considerable risks, have become important actors on this market.

This evolution has, according to Gillian Tett, lead to an increased accessibility of finance notably for companies that are in financial trouble. One remembers the negotiations between ‘financially challenged’ companies and banks for new loans (e.g. Swissair). This situation has, according to Tett, considerably changed in recent years: “[W]hereas these companies would have once been forced to turn to commercial banks [in order to obtain new loans], there is now a growing tendency for troubled companies to use hedge funds or other sources of capital […] (FT

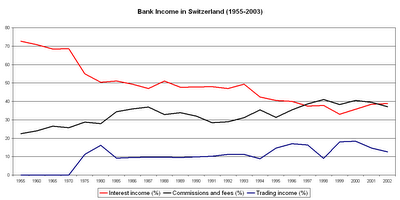

Now, what does this mean for the functioning of corporate governance? One important consequence is of course that the role of banks changes in important ways. Banks used to play a central role in the functioning of the economy especially in countries with strong universal banks – i.e. banks that are active both as commercial banks (loans) and investment banks (equity issuing etc.) - such as Switzerland and Germany. Universal banks grant loans to corporations, they issue equity for corporations, advise them in merger and acquisition activities and controlled, moreover, important portions of voting rights during the Annual General Meeting of these companies through a proxy voting system that allows them to vote for bank clients that did not wish to attend the AGM. This is why Continental European Corporate Governance Systems are usually called ‘bank-centred’ systems.

The central role of banks and their multiple channels of influence on industrial companies gave periodically rise to criticism of the power of banks and their damaging influence on industrial development. The most extreme theories postulated that banks consciously accepted the bankruptcy of a company that was under their controlled in order to get the maximum out of the company’s assets.

In

Be that as it may, the recent evolution of corporate finance led to a situation where industrial companies do not seem to rely so much on banks anymore, but they take out loans from other financial institutions or rise capital directly on equity markets (in the latter case, one speaks of disintermediarisation). Consequently, industrial companies are more and more independent from banks.

One important consequence of the disintermediarisation and the strategic reorientation of banks away from the loan business, which goes together with the increasing independence of industrial companies, is the anonymisation of relations between banks and industrial companies. In fact, credit activities are usually considered to be relationship-based activities, implying close personal ties between borrower and lender and an active monitoring by lenders of their loans. This was a central feature of Continental European corporate governance systems and limited the strength of market forces. Corporate finance through investment in equity, on the other hand, is market-based and does not necessitate any particularly close relationship between investor and issuer. This brings us to the downside of the increased independence of industrial companies from banks. By using more and more securitised finance instruments – as well for debt as for equity – companies become more dependent on financial markets. And this is precisely why we find so much change in corporate strategies in countries like

Friday, September 22, 2006

Boards of directors in the UK: structure, behaviour and competence. Or the limits of rules

Yesterday evening I was at a Round Table on Corporate Governance organised by the Centre for Research in Corporate Governance of the

1. The traditional system of cumulation between the positions of chairman and CEO (only 8.7% of the firms in their sample still had this board structure in 1997. Since then, this ratio has further decreased and is today probably about 2%)

2. A board with a full-time, executive chair who has formerly been CEO of the firm (20.6%)

3. A full-time, executive chair who has not been CEO of the firm (6.2%)

4. A part-time, non-executive chair who was formerly CEO of the company (10.6%)

5. A part-time non-executive chair who has never been CEO of the firm (53.7%)

The figures show that compliance with the governance codes is high since approximately 64% of the

Yet, McNulty argued convincingly that this compliance with the structure does not necessarily imply compliance with substance. In fact, the separation of the role of the Chair and the CEO aims at creating an independent board, which is supposedly able to effectively monitor the company’s management. However, McNulty and Pettigrew show that some of these models weaken, rather than strengthen, the position of the chairman and of the other NEDs on the board. Thus, their survey shows that only in models 1 through 3 the chair sets the agenda for the board meeting, whereas in models 4 and 5, i.e. the models that notably the Higgs report preaches, the CEO sets himself the agenda. The most likely explanation is that since the chair is a non-executive, he has not enough information about what is going on in the company in order to set the agenda.

The agenda setting is but one out of 34 issues of McNulty and Pettigrew’s research for which the respective power of the CEO and the chairman was analysed. All the results tend to show that board structures with non-executive chairmen reduce rather than increase the power of the chairman.

This result is actually confirmed by structural analyses of organisations. In fact, the claim that a large portion of board members should be NEDs may lead to an organisational structure, where the CEO is the only person to bridge the “structural hole” between the board and the operative management of the company. This of course gives him considerable brokerage power concerning the control of information flows between the board and the company as such. Whereas if other executive directors are on the board there is at least a theoretical possibility that the information the CEO gives to the board is verified by these executives. Hence, the complete independence of the board – i.e. 100% of NEDs – does not maximise the boards influence over management’s decisions.

Related to this, one issue that was brought up yesterday during the discussion, was the question of competence. In fact, the competence of board members is probably the most important factor, which can guarantee that a chairman, or any other NED, is able to effectively control the management’s decisions. Competence however can not be guaranteed with rules concerning the composition or the structure of the board but only with recruitment procedures for board members; and such procedures are difficult to define. How can one make sure that the shareholder meeting elects the “most able” candidate on the board? In most countries board composition is ruled by other criteria than competence. Thus in some countries legal rules prescribe board representation for certain constituencies of the firm (such as employees’ representation in

The link between competence of board members and effective control is an issue, which is virtually never addressed in discussions on good governance and does not appear as such in corporate governance codes or company laws. Of course finding a solution to this issue would greatly increase the quality of control mechanisms within the firm. However, as prof. McNulty pointed out last night, sometimes we can create as many new rules as we want, the outcome will always depend on how actors apply these rules and how they behave within the regulatory framework. This is a fundamental limitation to all efforts aiming at regulating the economy and making sure that things like Enron, Parmalat or Swissair do not happen again.

Friday, September 08, 2006

Princess Saurer, the Evil Hedge Fund, and the (Foreign) White Knight. Of how a Company Resists all Attacks…but Gets Eaten anyway.

Textile machinery and transmission system maker Saurer is used to fight – more or less successful – battles against potentially hostile investors. But the last one was particularly nasty! Since Laxey Partners, a

The fight between Saurer and Laxey Partners illustrates in an impressive manner the clash between these two conceptions of the stock company and shows that the shareholder value idea does not yet prevail in certain parts of the Continent. Industrialists – despite political discourse that indicate the contrary (cf. Franz Müntefering’s last year’s speech on the plague of locusts in Germany and the ensuing debate on capitalism) – still seem to have the means to defend themselves against the evil force of globalised capital (and especially its spearhead the hedge-funds)!

The story begins on

From this date on, Laxey started to exert pressure on the Saurer management. The main contentious issue is very revealing of what I called the clash of two different economic mindsets. Thus, the chairman of Laxey, Preston Rabl, argued that, even though the Saurer management did a good job, the company was undervalued on the stock exchange, which was – according to Rabl, due to the fact that the management retained to much cash for its investment projects (NZZ March 18, 2006). The remedy was hence to distribute this money to shareholders, to increase transparency concerning its acquisition policy, and possibly to review the structure of the company. Concretely, Laxey attacked the fact that Saurer was built around two pillars, which did not generate any synergies, i.e. a textile machinery and a transmission systems division.

Also, Rabl reproached the Saurer management with being inclined to engage into ‘empire building’, i.e. to acquire new companies in order to increase the company’s size without consideration for its value or profitability. This is of course a real danger in any company that works well and generates good money (as was impressively illustrated by Swissair’s McKinsey-made ‘hunter strategy’ during the 1990s). However convincing Laxey’s argumentation may appear from a shareholder’s perspective, the management of Saurer has compelling arguments as well. In fact, the management put forward that the two divisions – textile machinery and transmission systems – constitute a very good combination for the company’s stability. In fact, the textile machinery branch generates a lot of cash with only little investment. In the transmission technology branch, on the other hand, profit margins are higher, but more investment is needed (NZZ

This argumentation, in turn, is compelling from an industrialist’s point of view. However, shareholder value textbooks clearly state that diversification is not the role of the company, but of investors. Or in other words, by diversifying its activities in order to achieve a more stable course of business, Saurer reduces the profitability of the investors stake, who themselves have already diversified their portfolio.

Before the Annual general meeting of May 2006, Laxey increased the pressure by putting several points on the agenda for the AGM. Firstly, Rabl demanded a seat on the board of Saurer. Secondly, CHF 140m should be paid back to shareholders (through a capital repayment), and, thirdly, the company’s strategy concerning its internal and external growth strategy should be reviewed by external experts. The Saurer management rejected especially the second point of this agenda. In fact, according to them, the spare cash was needed for investments (i.e. acquisitions) in different parts of the world in order to consolidate Saurer’s position in these markets. Also the amount of CHF 140m was, according to the management, more than the company had in surplus, implying that the level of debt would have to be increased if this proposition was accepted by the AGM.

Who was right? Does the company’s management have the right to use profits in order to pursue growth strategies or does the undervaluation of the company constitute an expropriation of its owners? Hard to tell of course. Especially because this question is very much steeped with ideological considerations.

Be that as it may, on

However, despite Rabl’s election, the tensions between Saurer and Laxey did not decrease during the following months. In fact, it seems that the communication among the board members was very difficult. Thus, Rabl stated later that several important decisions were taken without even being discussed during board meetings (NZZ,

In the beginning of September, Laxey finally informs the public of its plans for Saurer. The most likely option that was considered was splitting Saurer into two, and selling one of the divisions (probably the transmission system business), and concentrating all the efforts on the other (NZZ,

However, on

Several observations can be made: Firstly, it is interesting to see that a supposedly so powerful hedge-fund did not achieve its goals despite the fact that Saurer constitutes – for Swiss standards – a rather open company respecting important corporate governance principles. Thus, Saurer applies since the early 1990s international accounting standards, it has a single share without restrictions to the exercise of voting rights or their transferability and it was not controlled by any large historical blockholder. Yet, the Saurer management still managed to repel the attacks. It is difficult to say what was decisive in this battle. In fact, the reasons for Laxey’s decision to stop the tug-of-war with the Saurer management and to sell its stake at a moment where it was about to obtain an extraordinary shareholder meeting are not completely clear yet.

A second observation is that Unaxis/Oerlikon – which made the headlines when it was taken over by the Austrian investors and when an additional considerable stake was acquired by a Russian investor – is welcomed by the Saurer management as “white knight”. Contrary to what usually happens in situations when Swiss companies are acquired by foreigners (cf. my previous post on this blog from

Sunday, September 03, 2006

The Power of Institutional Investors: What the Swissfirst – Bellevue Scandal Tells us about Corporate Governance in Switzerland

A new full-scale corporate scandal has emerged in

In fact, just before the merger of the two investment companies in September 2005, five large pension funds and two insurance companies sold their stakes in Swissfirst to this bank (NZZ, no 175,

The suspicion of insider trading is supported by the fact that during the month preceding the announcement of the merger the price of stock-options of Swissfirst evolved independently from the price of the underlying share. In fact, from the beginning of August 2005 through

One of the fund mangers appears to have increased hundredfold his personal fortune between 2001 and 2002. Following these revelations, the largest Swiss newspaper – the tabloid Blick – started a campaign against this fund manager. Front-page pictures showing the villa of the manager with headlines reading “That’s how the perkiest Swiss pension-fund manger lives” were published the following days and the integrity of the Swiss business elite as a whole was once more put into question.

But what does this episode tell us about corporate governance in

In the

Two reasons explain this complaisance of Swiss pension funds towards companies’ management. Firstly, there is a built-in lack of independence of private pension funds from companies’ management. In fact, the foundation board of a private fund is composed of representatives of the employees and of managers of the company it belongs to, which makes a critical stance towards the management of course unlikely. Yet there is a second reason why critical voices are rare in

These multiple personal ties between the actors in the Swissfirst scandal are typical for the very coherent Swiss business elite. It reminds also the Swissair debacle, where the board of directors was composed of the most illustrious personalities from business and politics, which met in different places of sociability. Such ties are one of the reasons why critical voices are very rare and why it is difficult for individual members of the elite to denounce wrong-doings. In fact, due to this coherence social control is strong, imposing a set of common values – such as loyalty – on the members of the business elite. This is of course not new in